Maybe one of architects’ most distinctive tasks is answering to questions. Now, there are two ways of answering; the first is to answer directly, like solving a problem, like proposing spaces to satisfy physical needs. We admit that this is maybe the most important and time-consuming way and it takes a lot of our own time andenergy too. There is, however, also a second way of answering, which is more indirect, more oblique, just brushing by reality, which, at the same time, means observing reality from a different standpoint. In this particular way of answering you shift a little bit from the answer, you avoid answering directly to a problem and play dump a little bit. This does not mean avoiding reality, this does not mean escapism, this means entering into reality from another door. We remember the words of the Greek poet Odysseas Elytis who asks for:

‘A small turn of the head

Which could mean a turn of the whole world’

This means that a change of perspective can trigger a change of understanding things, which may trigger in turn a transformation of the world, a personal one.

For us, a way of doing this is by using techniques and strategies that the narrative arts -like literature or cinema- use: metaphors, allegories, speaking in first person and telling a story, instead of describing scientifically a condition. This way of answering to a question through a story also appeals to people in a different way than a building does, maybe not as users but as people that have the gift of imagining and who want to use it, which is the need that literature, for example, appeals to.

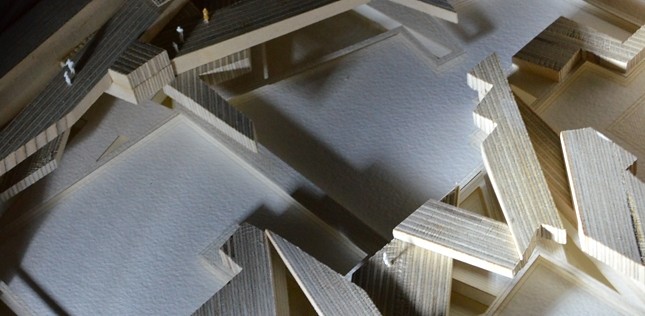

Our project consists of stories, drawings and models. The protagonist, who is an explorer that travels around a region of Athens, narrates the story in first person. In his travel he encounters imaginary tribes, each one of which has developed distinct habits and eccentric uses of space. Each tribe is also attached to a specific type of the urban environment of Athens. The block, the crossroads, the space between blocks, the unused patios within the blocks, are the prime materials through which the eccentricity of each tribe emerges: Pandionis worship a different god every week and use to burry him in their ‘Gods Cemetery’ by the end of the week. Erechteis are against finishing things and they celebrate their peculiarity in their ‘Unfinished Cathedral’. Hippothontis believe that they originate from the night sky and they want to have the stars and constellations glowing in their back yard in ‘Clair de Lune’. Leontis are sure that their dreams is a night-reality that is as real as the day-reality. Aiantis have built a wall around their block beyond which, they believe, is the realm of the gods, the animals and the dead, in ‘Pomerium’. The allegory of the tribes at each case refers -but is not limited- to human conditions, their relationship with each other and with their city: passions, fears, desires, dangers, needs, limitations and prejudices can be read between the lines of each story.

With the use of urban types of Athens and their imaginary transformation through narrative, we note that the city is made of a prime material, which can be transformed with the use of imagination. This may not be the architect’s major task, it is however as much important.

No comments:

Post a Comment